Data is changing the way lawyers litigate. Motion practice, a critical weapon in an attorney’s arsenal, is increasingly informed by statistical insight.

But data has yet to significantly impact how clients select their litigation counsel. Lawyer and law firm evaluation has traditionally been a subjective measure: driven by perception, personal relationships, and word-of-mouth recommendations. Typical of this subjectivity are law firm rankings from The American Lawyer, Above the Law, and The Vault, which survey attorneys for their impressions, and use simple metrics like revenue-per-lawyer.

This reliance on subjectivity is beginning to erode. Just as sabermetrics and Moneyball changed how sports teams evaluate prospective players’ skills — moving the analysis from simplistic and subjective measures to sophisticated and objective measures — litigation data is finally detailed enough, and legal technology robust enough, to provide an objective measure of lawyer and law firm skills. Lex Machina, for example, pioneered mining court dockets to gain actionable insights into patent litigation — a big step towards a more objective evaluation.

Yet that higher level docket-based analysis is still far removed from the more fundamental motion practice skills at the core of every litigation — the drafting and argumentation that go into the briefs filed in support of a court motion.

From Briefs To Law Firms

At Judicata we recently launched a tool called Clerk that analyzes and grades briefs, evaluating their strengths and weaknesses, looking for areas of improvement and attack. Clerk’s analysis spans seven dimensions that measure how well the brief is argued, how well it is drafted, and the context within which it arises.

Clerk can identify critical arguments that the parties missed (such as in a recent litigation over access to a California beach) and provide powerful predictive insight (such as in a recent Google pay discrimination lawsuit).

Clerk’s analysis is distilled into a single grade, where the higher the grade, the more likely it is that the brief will win. An interesting byproduct of this brief-level grading is that lawyers and law firms can also be graded on the same scale. By averaging a lawyer or law firm’s grades across a collection of their briefs, a clear picture of their litigation skill emerges. That grade can then be compared against other lawyers and law firms.

At Judicata we’ve compared briefs from the 20 largest law firms in California. These 20 law firms are among the 100 largest law firms in the world, and include firms in the global top 5.

Our evaluation involved running nearly 500 briefs filed in California state court through Clerk. The briefs spanned a diverse set of lawsuits, covering everything from individual employment actions, to complex contract disputes, to billion-dollar startup founder fights. The clients included young California companies like Lyft and Snapchat, Silicon Valley behemoths like Apple, Facebook, and Google, and international giants like BP and Toyota. Some of the lawsuits were highly publicized, and some involved well-known celebrities like Kim Kardashian, Carrie Fisher, and Manny Pacquiao.

The result of this evaluation is the first-ever ranking of law firm litigation departments based on an objective measure of their lawyering skills. Though the briefs we analyzed were all filed in California state court, the capabilities Clerk evaluates are fundamental to motion practice and translate to both federal court and other US jurisdictions.

Without further ado, Judicata’s 2018 law firm litigation ranking is:

Making The Grade

In addition to identifying clear differences in the motion practice skills of the different law firms, our evaluation also found that every single law firm has significant room for improvement. Some briefs were well-drafted, but poor on their argumentation. Other briefs were argued well, but their drafting was messy. And still others were weak across the board.

Clerk grades briefs on a numeric scale similar to that used by schools in the United States:

- 90–100

- 80–89

- 70–79

- 60–69

- 1–59

Briefs are scored on their Arguments, their Drafting and their Context. The individual scores on those three dimensions are then aggregated to produce a single overall grade.

Only one of the 500 briefs that Clerk analyzed scored what would be an A (actually, an A-). That was a brief filed by Erin Bosman and Julie Park of Morrison & Foerster.

Breaking It Down: Drafting

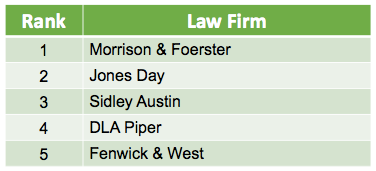

As part of our Clerk analysis we also identified the law firms that did best on the individual drafting and argumentation dimensions. On the drafting front, the five best law firms are:

Despite being better than the rest, these firms’ briefs were still at a level that would be unacceptable in other writing-focused professions (such as journalism). The difference is that while general purpose writing has spell-checkers and grammar-checkers, analogous legal-focused technologies are missing.

Nearly every brief we analyzed contained misspelled case names, miscited pages, and misquoted cases and statutes. Interestingly, about one third of the misquotes appear to be intentionally inaccurate.

More shocking was that eight of the law firms in our analysis filed briefs that misspelled their judge’s name (including some in the drafting top five). As an individual with an unusual name in the United States, I’m used to people writing “Itia” or even “Atari.” But it’s a glaring and automatic negative, and it creates a terrible first impression.

Yet fully 40% of the law firms in our analysis misspelled the name of the person who would ultimately decide to grant or deny their motion, and they did this on briefs which they probably were paid tens of thousands of dollars to research and write. Anne instead of Ann. Stephen instead of Steven. Ernst instead of Ernest. Deidre instead of Deirdre. And that’s just some of the misspellings in the first names.

In addition to reviewing spelling, quotations, and citations, Clerk also checked whether the briefs supported their legal principles with cases that reinforce their desired outcome. A defendant filing a motion for summary judgment should rely on case precedent where the defendant won — not where the opposing plaintiff won. Judges know to look for this, and often remark that a case relied upon by one party actually supports their opponent.

Most of the briefs in our analysis make the mistake of relying on precedent whose outcome supports the other side. Finding the right precedent to cite is hard. It’s a painstakingly manual task because it requires reading through hundreds of cases to find the right authority. Clerk is the first tool that can perform this check automatically.

Breaking It Down: Arguments

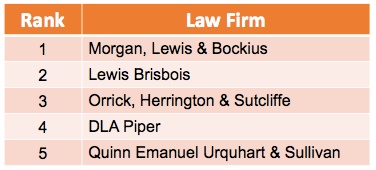

On the argumentation side, the five best law firms are:

On this dimension Clerk evaluated:

- How strongly the arguments raised in the brief favor the filing attorney’s side. The more the law appears to side with a party, the more likely that party is to win.

- How likely it is that the judge will distinguish or ignore the cases relied upon by a party. Judicata has calculated the vulnerability of each legal precedent and can measure how far out on a legal limb a brief is standing.

- How well-balanced the arguments in the brief are. Briefs need to both bolster their client’s position and undercut their opponent’s arguments. Being too one-sided in either direction isn’t good.

For situations where the context is unfavorable and the odds are stacked against the filing party — such as where the party is appealing a trial court decision or requesting a new trial — the quality of the argumentation is especially important.

Improving the argumentation can nearly double a brief’s chance of winning. When the argumentation fails to overcome the long odds of the brief’s context (by scoring less than 5 points higher than the grade given to the Context dimension), the chances of the brief winning are only about 20%. But where the argumentation greatly outperforms the brief’s context (by scoring 10 or more points higher than the grade given to the Context dimension), the odds of the brief winning rise to about 40%.

Although it shouldn’t come as a surprise, what this means is that better argumentation can produce better results. In other words, quality lawyering matters. That’s why clients seek out and pay for the best.

Closing Thoughts

We’re in the early days of a legal technology revolution. Paper is giving way to computers; unstructured content is giving way to structured data; subjective decision-making is giving way to objective analysis.

For clients, the impact of this change is that legal representation will get better and cheaper. Now that the quality of legal representation can be measured, it can finally be improved.

Editor’s Note: This article republished with permission of the author with first publication on Judicata.