Niklas Ohlrogge/Unsplash

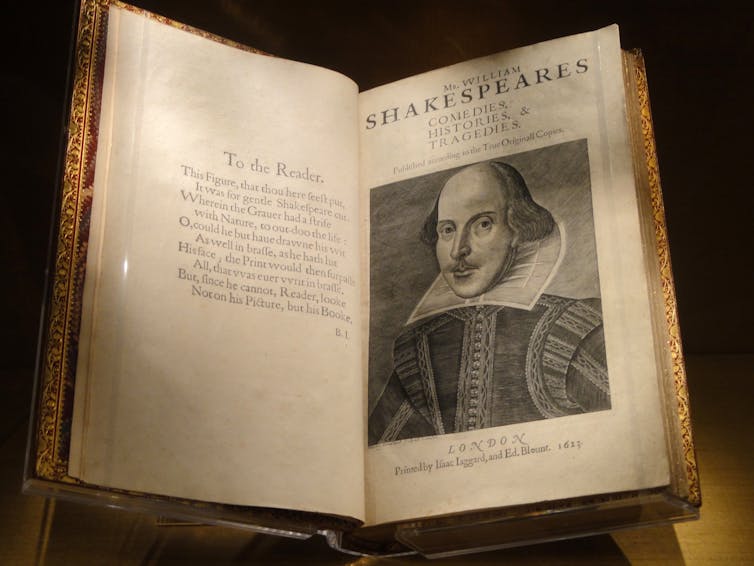

Right now, for technological, ethical and political reasons, the world’s archivists are suddenly very busy.Advances in digital imaging and communications are feeding an already intense interest in provenance, authorship and material culture. Two recent discoveries – a woman’s name scratched in the margins of an 8th-century manuscript, and John Milton’s annotations in a copy of Shakespeare’s First Folio held in the Free Library of Philadelphia – are examples of how new tools are revealing new evidence, and how distant scholars are making fascinating connections.

At the same time, and even more importantly, the holdings of archives, libraries and museums – “memory institutions” – are being scrutinised as the world grapples with legacies of racism, imperialism, slavery and oppression. Some of the holdings speak to heinous episodes and indefensible values. And some of them were flat-out stolen.

The so called “post-truth” era is a third cause of the burst of archival activity. Politicians and activists, mostly from the political right, have attacked facts and science. Archives have come under pressure to rewrite history, or have done so on their own initiative. The decision of the US National Archives to obscure anti-Trump slogans in a 2017 image of the Women’s March is a case in point.

Post-truth narratives pose all sorts of archival conundrums. In Australia, for example, people raised eyebrows when the National Library began collecting the posts of anti-vaxxers and conspiracy theorists, as part of its effort to document the COVID-19 pandemic.

Buffeted by strong and competing forces, archivists are in a tough spot. Their ability to navigate a path forward, moreover, is made more difficult by non-archivists’ foggy and unrealistic expectations of what archivists actually do, and what they might do in the future.

Daderot/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

What to save?

In principle, every detail of every kind of object is useful and valid as historical evidence. Two recent examples of this fractal property: the field of biocodicology – the study of biological traces in books and manuscripts – is turning library dust into valuable data, while the field of fragmentology is looking inside old book-bindings for hidden pieces of even older texts.

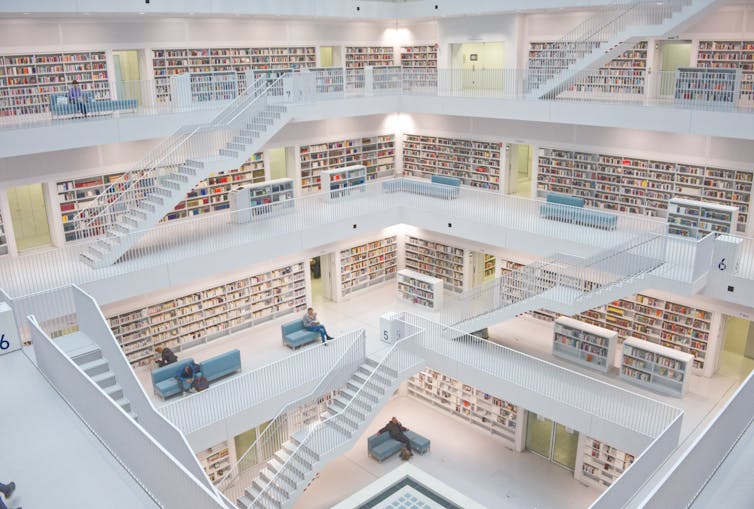

But this is not enough to justify keeping everything. And even if we wanted to, we couldn’t. In his story The Library of Babel, Jorge Luis Borges imagined an infinite library, but here on earth there are limits.

Despite the rise of e-books and online periodicals, publishers still produce millions of physical books, journals, magazines and newspapers every year. Then there are amateur publications, along with personal, official and commercial documents, multitudes of flyers, catalogues, posters and other ephemera. We can’t keep everything in this bulging pile of paper.

Jorge Luis Borges imagined an infinite library. Wikimedia Commons.

Non-textual objects are also part of the story of humanity, but we can’t keep all of them, either. Not only do we lack the room and money and curators to keep it all, for reasons of civilisational self-preservation we need to recycle as much of it as we can. And for reasons of civilisational sanity, we shouldn’t even attempt universal preservation, which – the moral of Borges’s story – is a sure-fire path to madness.

The physics of digital storage are different to those of physical archives, but ultimately the same rule applies: we can’t keep all the corporate and news sites, social media posts, blog posts, computer games, AI mash-ups, YouTube videos, messages, comments, selfies, porn – all of it growing by the second.

Keeping a single, static copy of the internet at any given moment is a Google-scale task. Now imagine what would be involved in preserving all the previous copies simultaneously, not just as static versions but dynamic ones, meaningfully accessible and covering every corner of the internet. That task is beyond even the imagination of Borges.

The minefield of decision-making

The work of archivists, therefore, necessarily involves decisions about what to preserve and for how long.

Those decisions are a minefield. Libraries, for example, are regularly criticised when they refuse donated books. “Why won’t you take our nineteenth-century bible,” the donors ask indignantly, “or our set of old racing guides, or Encyclopedia Britannica, or Funk and Wagnalls?”

Libraries and museums are criticised even more loudly when they are caught removing items from their collections. Every good curator knows the value of a regular cull, but patrons and funders have romantic conceptions of collection practices. Senior librarians get into trouble when people see, round the back of the library, the skips full of “deaccessioned” books.

In the global shift towards digital resources, libraries have been so trigger-happy in retiring physical holdings of newspapers and magazines, that some mastheads may no longer exist at all in physical form, their non-digital properties forever lost to research. Physical newspapers are not the only ones in trouble. Late in 2022, the National Library of Australia announced that funding for its hugely popular online newspaper archive Trove would likely run out in mid-2023.

Just as dangerous for librarians is the offloading – sometimes sheepishly, sometimes flagrantly – of valuable items via suave, big-city book dealers and auction houses, such as Christies and Sotheby’s.

In the 1980s, for example, at a time of tight budgets and financial austerity, the John Rylands Library in Manchester auctioned 98 of its best books on the grounds that they were “duplicates”. But a closer look revealed many of the books were unique in important ways. The sale sparked an outcry; author Nicolas Barker likened the disposals to the sale of a trilith from Stonehenge.

The benefits of hindsight

Librarians get in trouble when books leave – and when books arrive.

At the start of the 17th century, Sir Thomas Bodley revived one of the great Oxford libraries. He had firm ideas about what constituted “worthy books” for the revitalised collection. They certainly did not include “such books as almanacks, plays and an infinite number, that are daily printed, of very unworthy matters”. When Dr Thomas James, Bodley’s librarian, allowed such volumes into the collection, he earned a sharp rebuke. After Bodley’s death, James collected them with gusto.

With 400 years of hindsight, we can see Bodley’s definition of a worthy book was biased and fallible. His definition left out the first published works of Shakespeare, as well as many other early modern works of exceptional cultural and literary interest.

With our super-powered hindsight, we can also see that his 17th-century value judgements reflected explicit and implicit prejudices about class, gender, nationality, ethnicity, religion, high and low culture, and politics.

Of course, the same is true about curatorial judgements today. There is no such thing as an apolitical archive. Even an archive that is assiduously bipartisan or multi-partisan will still reflect choices about the scope and balance of the represented perspectives.

Right now, at our strange social moment, in which “woke” – a synonym for (racial) respect – is wielded as a politicised insult, archival work is even more political than usual.

Remi Mathis/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Danger areas

How things leave and how they arrive are just two of the danger areas for archivists. Archives are full of hazards, including light, air conditioners, thieves and careless handling.

Fakes are another danger. Bogus Socratic scrolls famously infiltrated the ancient Library of Alexandria. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Wrenn Library (subsequently in the University of Texas) and the British Library accumulated large holdings of Thomas Wise editions in the years before he was exposed as an audacious forger.

How should today’s archivists chart a course through this perilous terrain?

Most archival mistakes are the result of a failure to do something that is right but difficult, or doing something that is wrong but easy.

In the “easy but wrong” category, simple mistakes have led to the preventable damage of art, artefacts and books. The photo modification at the US National Archives was a grave dereliction of archival duty, but it was an easy path to follow, and technically a simple thing to do.

For an example of “difficult but right”, we need only consider that for much of the 20th century, Western “memory institutions” largely reflected a white and chauvinistic view of worthy items. It was hard for archivists to retain evidence from the cultural fringes. But many forward-looking archivists and institutions swam against the official and political tide, assembling collections focused on women, civil rights, banned books, queer literature and “low” literature, such as the cheap magazines known as “pulps”.

With hindsight, we can see that retaining and conserving those collections was emphatically the right choice. Banned and marginal texts are essential to several grand human projects, including filling in silences and erasures, and building foundations for a fairer and more inclusive society.

There are still obstacles to representation and inclusion, but the argument has largely been won. Recovering women’s history, decolonising the archive, queering the archive – these have all rightly become mainstream endeavours.

Contentious material

One of the most difficult frontiers for archivists today is whether and how to record social and political phenomena that progressive people would rather did not exist.

We have just come through the Trump era (or phase one of the Trump era) and we are still going through the COVID era. Both eras have spawned populist, sometimes militant and incendiary literatures and discourses.

In Melbourne, the State Library of Victoria is collecting pandemic-era imagery, including photos of anti-vax graffiti and anti-government protests. With the help of that library and other institutions, the National Library of Australia is keeping anti-vax, “pro-freedom” websites and social media posts.

Holding this kind of material is a challenge and a paradox for archives. The anti-vax sites are symptoms of anti-truth forces that are anathema to archives’ truth-telling goals. In the 19th century, the forger Thomas Wise relished the credibility that came from the British Library holding his publications. Now, the anti-vaxxers celebrate the official preservation of their material as a similar badge of legitimacy.

But no matter how obnoxious or fantastical, these records are historically relevant. They are part of the full story of politics and activism in Australia. For future scholars looking to understand the COVID era, the records will be invaluable.

Archivists cannot and should not blind humanity to its own mistakes. But the best archivists also know the importance of context when conserving and presenting difficult material. The records from the COVID fringe need proper and honest framing.

Such framing would acknowledge that the anti-vaxxers and conspiracy theorists did not represent a majority view, or even a significant minority one. It would also acknowledge the influence of misinformation and conspiracy theories beyond the fringe: on vaccine hesitancy, for example, and on the tactics of mainstream political parties that flirted with and even courted the anti-vax vote.

Darren England/AAP

The value of archives

Preserving the story of humankind: that is the noble goal of archives, libraries and museums. It can sometimes seem like an abstract luxury, but it is actually very tangible, and essential. Without evidence, there can be no history. And without history, we can’t understand ourselves or chart a good course into the future.

The clichéd image of archival work as dusty, dull and benign is a long way from the truth. Archivists are continually making hard decisions at the sharp edges of politics and social change.

What can society do to help? We need a wide conversation to better understand the nature and value of archival work, and the limits of what archivists can do. We need to give archivists an explicit licence and the necessary resources to continue to make difficult decisions.

For that to work, the community needs to protect archivists from politicians and narrow interests. Only then will archivists feel safe to be transparent about what they are keeping, why they are keeping it, and the judgements they are applying in order to put the holdings in their proper context.

Looking back over the past two millennia, archivists have made every kind of curatorial mistake. They have rejected worthy items, let in unworthy ones, mishandled objects in their care, and fallen prey to fakers and frauds. But only rarely have they lost sight of their core purpose.

On the big issues of our time, we should trust archivists to make the right calls. And we should give them our understanding and protection so they can do their work in peace.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.