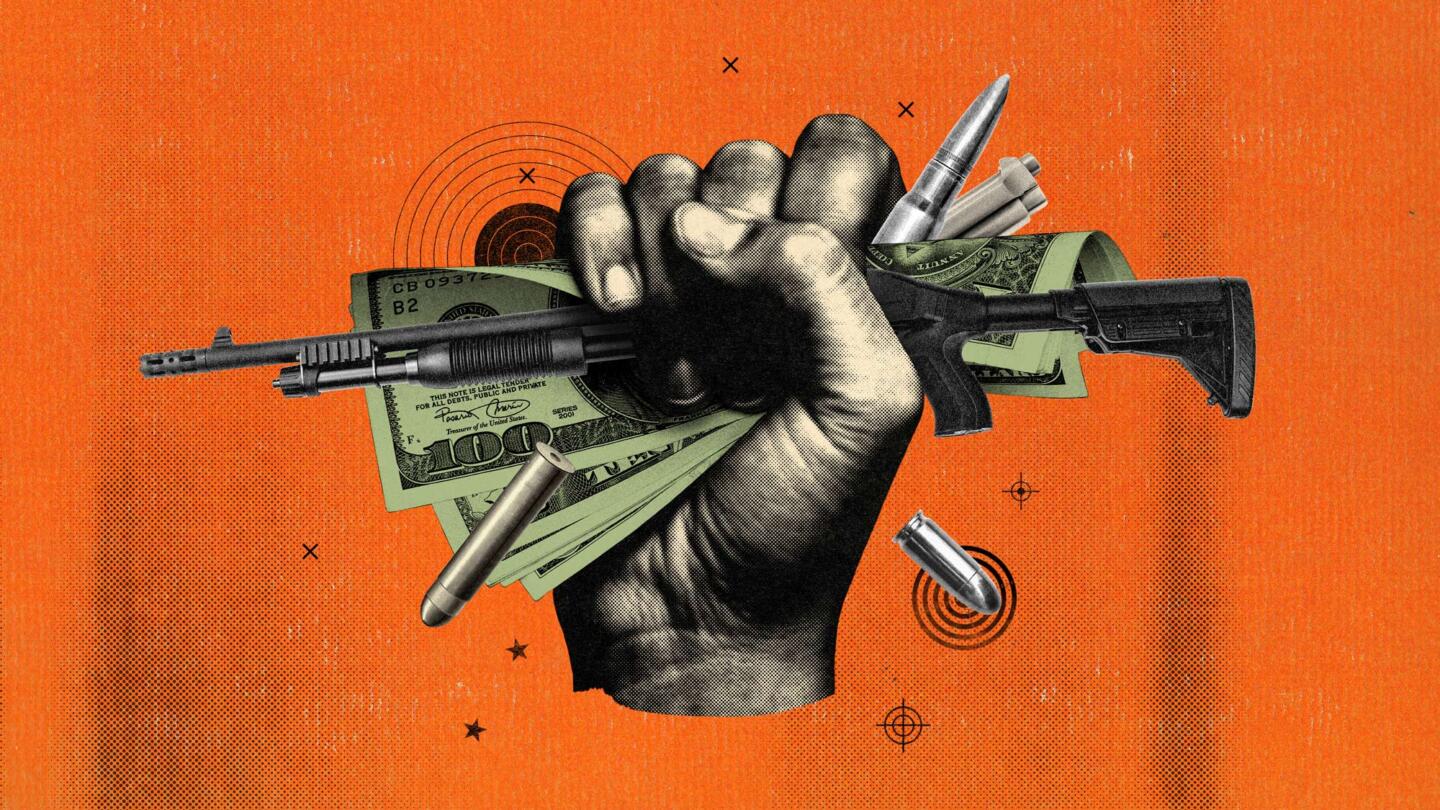

CalMatters and The Markup used Facebook’s AI model to count the millions of dollars it makes after violent news events

After the attempted assassination of Donald Trump in July, the merchandise started showing up on Facebook.

Trump, fist in the air, face bloodied from a bullet, appeared on everything. Coffee mugs. Hawaiian shirts. Trading cards. Commemorative coins. Heart ornaments. Ads for these products used images captured at the scene by Doug Mills for the New York Times and Evan Vucci for the Associated Press, showing Trump yelling “fight” after the shooting. The Trump campaign itself even offered some gear commemorating his survival.

As the Secret Service drew scrutiny and law enforcement searched for a motive, online advertisers saw a business opportunity in the moment, pumping out Facebook ads to supporters hungry for merch.

In the 10 weeks after the shooting, advertisers paid Meta between $593,000 and $813,000 for political ads that explicitly mentioned the assassination attempt, according to The Markup’s analysis. (Meta provides only estimates of spending and reach for ads in its database.)

Even Facebook itself has acknowledged that polarizing content and misinformation on its platform has incited real-life violence. An analysis by CalMatters and The Markup found that the reverse is also true: real-world violence can sometimes open new revenue opportunities for Meta.

While the spending on assassination ads represents a sliver of Meta’s $100 billion-plus ad revenue, the company also builds its bottom line when tragedies like war and mass shootings occur, in the United States and beyond. After the October 7th attack on Israel last year and the country’s response in Gaza, Meta saw a major increase in dollars spent related to the conflict, according to our review.

Tech advocacy groups and others question whether Facebook should even profit from violence and whether its ability to do so violates the company’s own principles of not calling for violence. The company said advertisers often respond to current events and that ads that run on its platform are reviewed and must meet the company’s standards.

If you count all of the political ads mentioning Israel since the attack through the last week of September, organizations and individuals paid Meta between $14.8 and $22.1 million dollars for ads seen between 1.5 billion and 1.7 billion times on Meta’s platforms. Meta made much less for ads mentioning Israel during the same period the year before: between $2.4 and $4 million dollars for ads that were seen between 373 million and 445 million times. At the high end of Meta’s estimates, this was a 450 percent increase in Israel-related ad dollars for the company. (In our analysis, we converted foreign currency purchases to current U.S. dollars.)

The American Israel Public Affairs Committee, a lobbying group that promotes Israel, was the major spender on ads mentioning Israel. In the six months after October 7th, its spending increased more than 300 percent over the previous six months, to between $1.8 and $2.7 million dollars, as the organization peppered Facebook and Instagram with ads defending Israel’s actions in Gaza and pressuring politicians to support the country.

As the war has roiled the region, AIPAC paid Meta about as much for ads in the 15 weeks following October 7th as the entire year before.

“Our effort is directed to encouraging pro-Israel Americans to stand with our democratic ally as it battles Iranian proxies in the aftermath of the barbaric Hamas attack of October 7th,” Marshall Wittmann, a spokesperson for AIPAC, said in an emailed statement.

Other ad campaigns mentioning Israel supported different sides of the conflict. Doctors Without Borders, for example, used advertising to highlight the humanitarian crisis in Gaza. Other ads defended and promoted Israel. The Christian Broadcasting Network tied the October 7th attack to a claim in an ad that Iran’s “final, deadly goal” was “to establish a modern caliphate—an Islamic-founded, tyrannical government—across the world.”

Meta, the parent company of Facebook and Instagram, takes in the vast majority of its revenue from targeted advertising. The company tracks users online to profile their habits and, when a business or organization wants to reach them, lets those businesses pay to send ads to people who might be interested. Those ads might be tied to something perfectly wholesome, like gardening. But the company’s algorithms don’t distinguish between simple hobbies and something darker.

Meta spokesperson Tracy Clayton said in an emailed statement that Meta did not ultimately profit from political violence, as advertisers broadly back away from advertising during times of strife for fear their ads will be promoted alongside news of the violence.

Clayton noted Meta’s chief financial officer recently said on an earnings call that it is “hard for us to attribute demand softness directly to any specific geopolitical event” but had seen lower ad spending “correlating with the start of the conflict” in the Middle East, and had seen similar at the start of the war in Ukraine.

“Advertisers responding to current events are nothing new, and it’s seen across the media landscape, including on television, radio, and online news outlets,” Clayton said. “All ads that run on our platform must go through a review process and adhere to our advertising and community standards, and Meta offers an extra layer of transparency by making them publicly available in our Ad Library.”

CalMatters and The Markup used Meta’s own tools to calculate how much Meta makes from spikes in advertising when instances of political violence happen, reviewing thousands of ads through both manual review and with the assistance of an AI model offered by Meta itself. (We also made improvements to Meta Research’s scripts for accessing the Ad Library API, and we’re sharing our changes.)

To examine the assassination attempt merchandise, we ran a simple search of Meta’s Ad Library for ads that mentioned “assassination,” including any in our analysis that also mentioned “Trump” and hundreds of others that didn’t mention the former president by name but were clearly related to the shooting.

“First they jail him, now they try to end him,” one ad read. A conspiratorial ad for a commemorative two-dollar bill claimed “the assassination attempt was their Plan B,” while “Plan A was to make Biden abandon the presidential campaign.” Some ads used clips from the film JFK to suggest an unseen, malevolent force was at work in the shooting.

Gun advocates paid for ads, using the assassination attempt as a foreboding call to action. One ad promoting a firearms safety course noted that “November is fast approaching.” A clothing business said in an ad that, since “the government can’t save you” from foreign enemies, Americans “need to be self-reliant, self-made, and self-sufficient.”

“Because when those bullets zip by, you are clearly on your own,” the ad read.

Most of those ads did not appear to violate Meta’s policies, although some may have broken its ban against showing weapons while alleging “election-related corruption.” But even the ones that didn’t clearly violate Meta’s rules still place the company in an uncomfortable position, as the business takes in advertising dollars from posts tied to grim news cycles.

CEO Mark Zuckerberg himself commented on the first Trump assassination attempt, saying in an interview that it was “one of the most badass things I’ve ever seen in my life.” Trump has now survived a second apparent assassination attempt, and Zuckerburg’s company has made millions of dollars through political advertising tied to these and other violent acts.

Katie Paul, director of the Tech Transparency Project, a nonprofit advocacy organization, said “it’s not a surprise” that ads around political violence would pop up after incidents “if Meta is not making any effort even on a good day to effectively enforce their policies.”

“There’s huge problems with their advertising broadly,” she said. “They’re profiting off of a lot of harmful things, really without any sort of repercussions.”

A Trump-fueled business and cash from war

Many businesses paying for the assassination ads sold pro-Trump gear before the shooting — and some might have spent a similar amount on ads if the shooting never happened.

But for some, the assassination attempt effectively became an entire business strategy, according to the review of Meta advertising data.

A clothing company called Red First, which offers everything from customized shirts for pet owners to flags saying “Hillary belongs in prison,” offered assassination-related merchandise through a network of pages with names like 50 Stars Nation and Red White and Blue Zone.

The company, which operates in California and Vietnam, according to Meta’s required disclosures, has spent more than $1.8 million since February 2023 to promote ads through its various pages. But in the wake of the shooting, the company pivoted to merchandise around the event.

Red First’s ads were relatively innocuous compared to some that sprang up after the shooting – they promoted Trump, not the shooting, and not the idea of retaliation for it. One shirt showed an illustration of Trump, middle fingers in the air, and the words “you missed bigly.” The company has also offered Kamala Harris merchandise, recently launching a page dedicated to it as well.

But the ads related to the shooting simultaneously sold products, promoted Trump, and let Meta reap advertising cash from the incident.

Many of the thousands of ads posted by the company didn’t explicitly use the word “assassination,” but clearly referenced the event in other ways, using slogans like “he will overcome,” “fight fight fight,” “legends never die,” and “shooting makes me stronger.”

CalMatters and The Markup

To suss out which ads were related to the shooting, we reviewed more than 4,200 ads from the company’s different pages with the assistance of a large language model named Llama, a Meta AI model.

We programmed the model to evaluate the text of each ad to determine whether it was related to the assassination attempt, then manually reviewed hundreds of its classifications to ensure it was working as expected.

After our review, we determined that more than 2,600 of those more than 4,200 ads were related to the assassination attempt. The total Red First paid to Meta in the 10 weeks after the shooting for those ads: between $473,000 and $798,000.

Red First lists a phone number and street address in Southern California, but didn’t respond to phone or email, and the listed address is for a mail-opening service.

The NRA and violent ads around the globe

The advocacy organization the Tech Transparency Project has charted how the National Rifle Association has paid to promote pro-gun views on Meta and Google’s ad platforms after mass shootings. Despite calls from tech company executives for gun control, those companies profit from NRA spending that spikes after shootings, the group has pointed out.

After the mass school shooting in Parkland, Fla., the NRA increased its spending on Google and Facebook ads, the Tech Transparency Project noted in one report. In 2018, the year of the shooting, Meta received “more than $2 million in advertising fees from the NRA starting in May of that year,” the report found, which also found that “NRA ad spending reached its highest levels on Google and soared on Facebook” following a week of mass shootings the following year that left dozens of people dead.

Just days before the January 6th insurrection, the Tech Transparency Project found that Meta hosted ads offering gun holsters and rifle accessories in far-right Facebook groups.

Internationally, Meta has often lapsed in its pledge to keep violent content off its platforms.

Meta’s ad policies forbid calling for violence. But when faced with crucial tests of its content moderation practices, the company has repeatedly failed to detect and remove inflammatory ads. A 2018 report, commissioned by Facebook itself, found that its platform had been used to incite violence in Myanmar, and that the company hadn’t done enough to prevent it.

Alia Al Ghussain, a researcher on technology issues at Amnesty International, said that as troubling as some ads might be in English, ads in other languages may be even more likely to pass Meta’s content moderation. “In most of the non-English-speaking world, Facebook doesn’t have the resources that it needs to moderate the content on the platform effectively and safely,” she said.

Despite later admitting responsibility for violence in Myanmar, the company continues to be faulted for gaps in its international moderation work. Another advocacy organization found in a test that the company approved calls for the murder of ethnic groups in Ethiopia. More recently, a similar test by an advocacy organization found that ads explicitly calling for violence against Palestinians—a flagrant violation of Meta’s rules—were still approved to run by the company.

“If ads which are presenting a risk of stoking tension or spreading misinformation are being approved in the US, in English, it really makes me fearful for what is happening in other countries in non-English-speaking languages,” Al Ghussain said.

This article was originally published on The Markup and was republished under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives license.