Artificial Intelligence is increasingly the talk of the town in legal tech circles. From the International Legal Technology Association Conference in Las Vegas, Nevada, to the American Association of Law Libraries Conference in Austin, Texas, AI has been at the center of more than a dozen presentations and panels in recent months.

Yet for all the discussion of impending disruption caused by AI — in both law and in the broader world beyond — relatively little has been said about how artificial intelligence technologies work, what they are good (or bad) at, and what that may mean for high-stakes fields like law.

Artificial Intelligence — “the capability of a machine to imitate intelligent human behavior,” as Merriam Webster defines it — has witnessed incredible growth and progress in the last several years. At its core are advances in Machine Learning, algorithms that learn from processing enormous amounts of data to extract common patterns. In recent years, a technique called Deep Learning has catalyzed major breakthroughs in diverse fields like computer vision, speech recognition, language translation, and game play (in particular, Go).

The progress of these algorithms is real and impressive, and advances are being made daily. But while the media attention has been positive (and generally justifiably so), it often has spurred misinformation and hype that far outpaces what is actually happening on the ground.

How Much Is Ten Minus Two?

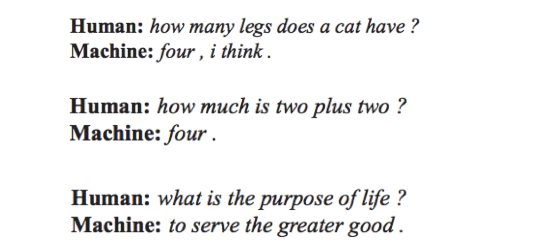

In 2015, Google published a research paper titled A Neural Conversational Model. They had built software (known as a “chatbot”) that was trained on old movie scripts to emulate human dialogue. The paper included a long back-and-forth transcript where a person asked a question, and the software returned an answer. Selections from the exchange included:

Clearly these are intelligent sounding responses, so it may come as no surprise that WIRED magazine wrote an article on the paper under the headline:

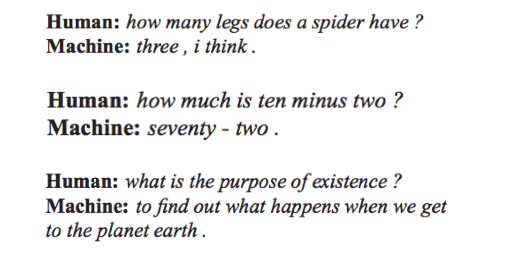

But is that really what was going on? Consider these other exchanges from the paper:

From this exchange, an alternative (and just as accurate) headline could have been:

So how do these two sets of answers emerge from the same software? How can it be both brilliant and boneheaded at the same time?

This inconsistency is due to what the software is really doing when it responds to a question, and, more importantly, what it is not doing. The chatbot is parroting statistical patterns it discovers in the words and phrases of the data it is trained on. Learning patterns requires enormous amounts of data, with typical training sets measuring in the millions of examples.

With that in mind, the different performance on “two plus two” and “ten minus two” makes more sense when one considers that the former phrase is significantly more common than the latter. According to Google, the former is found in roughly 100 times as many books and web pages.

What the software is not doing is understanding that the question is a math problem, performing a calculation, and providing the answer. Nor is it debating the meaning of life. In fact, it has no understanding of what “life” is, and it does not know how to “debate.”

This is not to denigrate the technology or the advances being made, but rather to point out that understanding what the software is doing is important to evaluating the claims being made.

The Cost of Being Wrong

Equally important for evaluating artificial intelligence technologies is understanding the domain in which the technologies are being used. For some use cases machine learning can be a great fit.

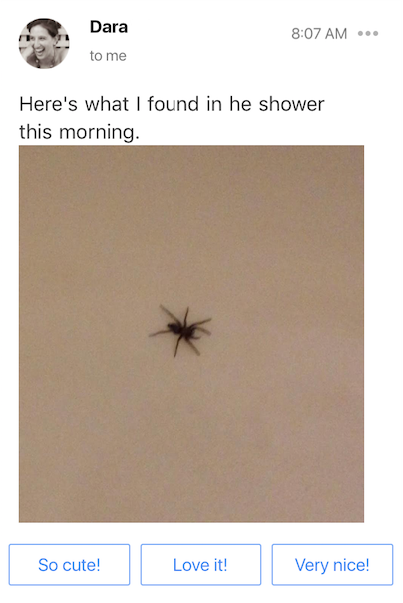

Consider, for example, the automated replies that Gmail recently started suggesting to users at the bottom of their emails. These are pithy responses that a user clicks on to avoid typing out a reply themselves. There are minimal negative consequences if the suggestions occasionally look like this:

Other than taking up screen real estate, they are pretty harmless and occasionally provide good comic relief. Moreover, it’s easy to increase the chances of a useful suggestion by presenting three options, rather than just one.

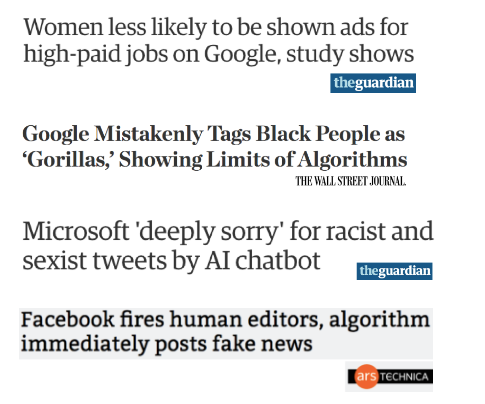

But not every area is equally amenable to machine learning, since the errors coming out of machine learning systems are not always so benign. A few of the more distressing machine learning blunders from the last couple years include:

These headlines reflect serious failures. Those failures should be a big cause for concern when courts are using machine learning to inform decisions about bail, sentencing, and parole (a practice that is distressing and should be stopped).

The False Positive Paradox

The greater the consequences the more important it is to understand how and why machine learning systems get things wrong.

Take an area people are generally familiar with: medical diagnosis. We all get tested for various conditions and diseases throughout our lives. Not surprisingly, the tests sometimes come back wrong.

Medical tests exhibit two kinds of errors:

- False Positives: where the test incorrectly identifies the presence of what the test is looking for.

- False Negatives: where the test incorrectly identifies the absence of what the test is looking for.

Developing a good test requires balancing these types of errors. At one extreme, a test could always indicate that a condition is present. Although the test would never produce any False Negatives, it would return many False Positives. At the other extreme, a test could always indicate that a condition is absent. The test would not produce any False Positives, but it would lead to many False Negatives.

Real-world tests fall somewhere in between these extremes. For understandable reasons, most medical tests heavily favor erring on the side of returning a False Positive, since the opposite could mean missing a diagnosis.

But a little understood issue is that even if a test is very accurate, the test can still lead to a large number of False Positives or False Negatives.

Consider a disease that affects only one out of every 10,000 people. Suppose there is a test for that disease that is correct 99% of the time: if you have the disease, the test shows that you do have it 99% of the time; and if you do not have the disease, the test shows that you do not have it 99% of the time.

While at first blush it may seem that a person who tests positive for the disease has a 99% chance of having the disease, the reality is very different. Despite the test being 99% accurate, the probability that an individual who has tested positive will actually have the disease is 1%.

How is this possible? Consider testing a group of 10,000 people where only one person has the disease. Because the test is 99% accurate, that one person will likely be identified as having the disease. Of the 9,999 people without the disease, the 99% accuracy means that 9900 people will correctly test negative and 99 people will falsely test positive. So we’ll have 100 positive tests, but only one person with the disease. Thus, the probability of an individual who has tested positive actually having the disease is only 1%.

This phenomenon is known as the False Positive Paradox and it extends far beyond the field of medical diagnosis. It has big implications for both machine learning and legal technology.

False Positives In The Law

Obviously, legal decisions do not get diseases, but they may be unhealthy in their own way — by containing inaccurate, or “bad,” law. Identifying cases that have bad law is a classification problem that runs up against the False Positive Paradox.

Consider a bad law classifier that is 94% accurate (which is the accuracy of Google’s state of the art language processor SyntaxNet).

In California, about 6% of judicial decisions contain bad law. Given 1000 cases where 940 cases are good law and 60 cases are bad law, the classifier will identify 884 of the good law cases as good law and 56 of the good law cases as bad law (94% of 940 and 6% of 940, respectively). The classifier will also identify 56 of the bad law cases as bad law and four of the bad law cases as good law (94% of 60 and 6% of 60, respectively). So the software will identify 112 cases as bad law, but only 56–50% — will actually be bad!

This is problematic since lawyers have a duty to argue only good law, and the failure to do so can lead to significant repercussions, including court sanctions.

riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s

While the False Positive Paradox is one way a machine learning system can be wrong, it doesn’t explain why “ten minus two” equals “seventy — two.”

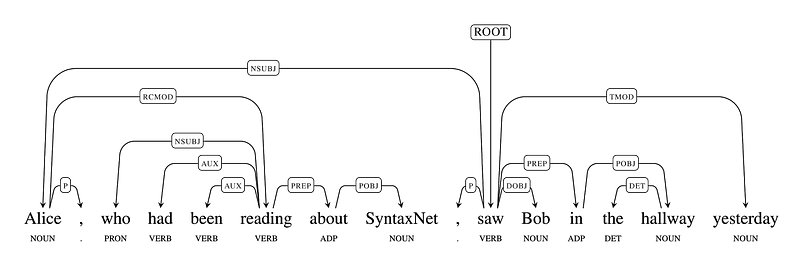

As noted above, one of the leading language processing programs is SyntaxNet, a machine learning tool that Google open-sourced last year and which it claims is “The World’s Most Accurate Parser.”

SyntaxNet identifies the underlying structure of a sentence:

It uses statistics to identify the dependencies between words in a sentence — “linking” them and labeling their grammatical functions. SyntaxNet does this with roughly 94% accuracy.

But while the software is, in some ways, reading, the reality is that it isn’t understanding. SyntaxNet does not have a model of the world from which to connect written words to concepts. Without knowledge and a representation of the real world, the software perceives little difference between the first sentence of James Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake:

riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s, from swerve of shore to bend of bay, brings us by a commodius vicus of recirculation back to Howth Castle and Environs.

and a sentence from a legal decision:

The authorities cited by Bay Shore are to the effect that only the court sitting in probate could award a commission to Maykut payable by the executor.

Both sentences have underlying grammatical structures. To SyntaxNet the only difference is the words used and how they’re linked. The fact that one sentence is idiosyncratic stream-of-consciousness and the other is a legal statement is lost.

Errors Compound

Properly representing and understanding written legal text requires more than just SyntaxNet — it requires understanding everything from the mundane, like accurately recognizing sentence boundaries, to the knowledgeable, like recognizing names and entities, to the contextual, like placing events in their proper time.

Doing this automatically requires stacking many layers of code, where each layer is targeted towards automating a different piece of the puzzle. A comprehensive system will have more than a dozen layers that need to be integrated.

The challenge with such a system is that the errors in each layer compound. If each layer is 94% accurate, and there are twelve layers, then the accuracy of the whole system will only be 48%:

94% x 94% x 94% x 94% x 94% x 94% x 94% x 94% x 94% x 94% x 94% x 94% = 48%

Learning To Fly

So what does that mean for machine learning and software in the legal industry? Is it all doom and gloom for machine learning in the law?

Not at all.

It just means that in order to use machine learning properly, legal technology has to have a healthy respect for error. Fortunately, we can find guidance from another industry: airline travel.

Airplane crashes are extremely rare. This is because society has utilized techniques that minimize risks over time. These have made flying an incredibly safe form of transportation today.

Two of the most important airplane safety techniques are redundancies and black boxes. At Judicata we’ve built systems modeled on both of these ideas.

Redundancies are backup systems that kick-in if the main system fails. Backup systems must be independent and have different failure scenarios. If the same failure can take down both the primary and secondary systems, then you don’t have a redundancy.

At Judicata we have many redundancies built in, a couple of which are especially relevant to the case law classification problem discussed above.

First, in addition to using software like SyntaxNet that parses the links between words in a sentence, Judicata also leverages a second program that understands language in a very different way: based on hard-coded grammatical rules. Pairing these two algorithms together greatly increases our language processing accuracy and the understanding we have of the judicial decisions we work with.

Second, we don’t rely on automation alone for our classifications. We pair our software with human review. Having a system that enables (and encourages) human intervention allows us to produce classifications that are much more accurate, and can remedy even the most egregious software errors.

Black boxes on airplanes continuously record the state of the instruments on an airplane. (For redundancy reasons, each airplane has two black boxes.) This data enables investigators to understand why something went wrong after an incident. The purpose of the black box is not to prevent the initial failure, but rather to make learning possible and to prevent future incidents. Airline safety continues to improve because there is a continuous learning process focused on understanding failures.

At Judicata we make the underlying data that goes into our automated determinations internally visible via “debug” windows. Moreover, the data is expressed in a way that is comprehensible to both engineers and non-engineers alike. By having our software’s decision making broadly accessible, we’re able to understand errors and fix them quickly. This leads to continuously improving software that is ultimately more accurate, reliable, and robust.

Closing Thoughts

The use of artificial intelligence and machine learning in the law is in its infancy. In the coming months and years much progress will be made, and there will be bold predictions that come true.

But it is important to get past the hype around artificial intelligence and machine learning, since there is a big downside. Recognizing the limits of artificial intelligence and machine learning is a critical step towards using those technologies well. Notwithstanding the impression people may have, building reliably intelligent legal software requires more than just the application of the latest trendy tools. It requires building systems that are robust and that respect the use cases for which they are designed.

As the saying goes: if all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. Machine learning is a hammer, but not everything is a nail.

Editor’s Note: This article is published with the permission of the author, with first publication on Medium’s Judicata blog.